This Friday we’re so pleased to open Remembering Gene Wilder at the Royal in West L.A. and the Town Center in Encino. A loving tribute that celebrates the life and legacy of the comic genius behind an extraordinary string of film roles, from his first collaboration with Mel Brooks in The Producers, to the enigmatic title role in the original Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory, to his inspired on-screen partnership with Richard Pryor in movies like Silver Streak. It is illustrated by a bevy of touching and hilarious clips and outtakes, never-before-seen home movies, narration from Wilder’s audiobook memoir, and interviews with a roster of brilliant friends and collaborators like Mel Brooks, Alan Alda, and Carol Kane. Remembering Gene Wilder shines a light on an essential performer, writer, director, and all-around mensch.

We have several introductions and Q&As scheduled with executive producer Julie Nimoy, writer Glenn Kirschbaum, and Mr. Wilder’s widow Karen Wilder.

“A hugely enjoyable walk through Gene Wilder’s entire life” – The Broad Street Review

“Tender and eye-opening tribute.” – Jewish Film Institute

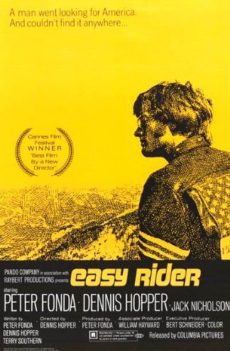

![Tickets: http://laemmle.com/film/suburbia | Subscribe: http://bit.ly/3b8JTym | When household tensions and a sense of worthlessness overcome Evan, he finds solace with the orphans of a throw-away society. The runaways hold on to each other like a family until a tragedy tears them apart.

Tickets: http://laemmle.com/film/suburbia

RELEASE DATE: 7/24/2024

Director: Penelope Spheeris

Cast: Bill Coyne, Chris Pedersen, Jennifer Clay, Timothy Eric O'Brien, Wade Walston, Mike B. The Flea

-----

ABOUT LAEMMLE: Since 1938, Laemmle [Theatres] has been showing the finest independent, arthouse, and international films.

Subscribe to Laemmle's E-NEWSLETTER: http://bit.ly/3y1YSTM

Visit Laemmle.com: http://laemmle.com

Like LAEMMLE on FACEBOOK: http://bit.ly/3Qspq7Z

Follow LAEMMLE on TWITTER: http://bit.ly/3O6adYv

Follow LAEMMLE on INSTAGRAM: http://bit.ly/3y2j1cp](https://90bb70.p3cdn2.secureserver.net/wp-content/plugins/feeds-for-youtube/img/placeholder.png)