We open the beautiful new Italian film The Macaluso Sisters this Friday at the Newhall, Playhouse, Royal and Town Center, as well as August 20 at the Claremont. As of this writing, Emma Dante’s movie, about how a tragedy changes the lives of five sisters in Palermo, boasts a rare “100% Fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes, with praise such as:

“Haunting and powerful.” (New York Times);

“In just her second feature after the taut street-stand-off drama A Street In Palermo seven years ago, Dante sets a firm seal upon her cross-disciplinary emergence as a director of unusually vivid empathy.” (Variety);

“Dante’s film, beautifully done, is never more resonant than when reminding us of the lingering impact of childhood drama and the devastating nature of childhood trauma.” (Times [U.K.]).

Unfortunately, our usually excellent hometown daily erred and did not assign a film critic to publish a review. To make up for it, here’s the entirety of Beatrice Loayza’s full New York Times Critic’s Pick review:

“No mere sun-kissed coming-of-age film, The Macaluso Sisters opens on a blissful day filled with young love and beachside longing that is tragically upended by an accident that has everlasting reverberations.

“The Italian filmmaker Emma Dante, best known as a director of avant-garde theater and opera, adapted the film based on her acclaimed play of the same name. Here, she imagines the ripple effects of a sister’s death across generations with metaphysical grace and hints of fantasy, straying from the plot-reliant mold of most human dramas toward something more haunting and powerful.

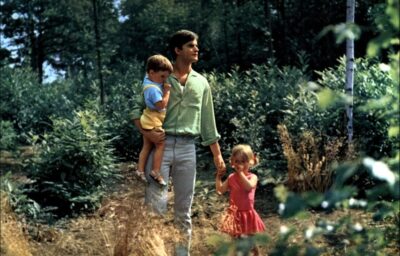

“Five orphaned sisters — Katia, Lia, Pinuccia, Maria, and Antonella — live alone in a lively apartment in Palermo, Sicily, where they sustain themselves by loaning out pigeons for ceremonies and events. On their day off, they head to the beach, passing through a field peppered with enormous dinosaur figurines and initiating a pop music-scored dance party upon their arrival. These magical moments are grounded by the cinematographer Gherardo Gossi’s tactile photography, which accentuates the youthful vitality of the sisters’ bodies and the playful chaos of their movements.

“Following the death of a sister, Dante skips ahead to a future in which the group — now played by a different group of actresses — are middle-aged and broken, each in their own particular way. They remain in the same apartment, while ghostly manifestations of their missing sister create a stark contrast between their aging bodies and those of their brimming younger selves.

“A third act shows three sisters in old age and in mourning. Yet the apartment and its white cabinet — adorned with an etching of a beach — looks the same. By the end, Dante stages a transcendent confrontation with the impermanence of the body, destined to degrade, yet sustained by the memories and relationships that have come to define it.”

We are proud to open Ira Deutchman’s excellent new movie about the American art film exhibition business, Searching for Mr.Rugoff, on Friday, August 13 at the Monica Film Center. In The New Yorker, Anthony Lane wrote, “Searching for Mr.Rugoff is an entertaining and instructive jaunt, and it bristles with small shocks.” In Owen Gleiberman’s Variety review, he described it as “an enthralling documentary that movie buffs everywhere will want to see…as essential as any chapter of Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. Ira wrote the following for us:

Searching for Mr. Rugoff, the documentary film that I made and that is opening around the country in August, is the story of a colorful and difficult person who personified the kind of characters who helped to create the art film business as we know it today. In focusing on this particular person, I in no way meant to imply that he was alone in these pursuits. In fact, the project originated as what I thought was going to be an oral history of the art film business as it matured in the 1960’s and 70’s. I ended up focusing on Rugoff because, as a former employee, it was a story that I thought I could tell, but I also interviewed a number of other key figures from that period including Dan Talbot, Meyer Ackerman, Randy Finley and Bob Laemmle.

The thing these folks all had in common was a love of movies and a keen awareness of the tastes and appetites of their own audiences. The business at that time was very much a local enterprise. The success of a particular cinema was a function of location, carving out a specific identity and having the creative energy to make people aware of what was playing. While the distributors would provide a menu of films and the materials to market them, it was up to the local exhibitors to engage directly with the audience. The best exhibitors were the ones who were the most creative in that endeavor. We refer to this now as “old fashioned showmanship,” but it was hardly old-fashioned at the time. It was a critical part of the business. This was even true for major studio films.

This all changed in 1975, when Jaws was released nationally and became a phenomenon. Distributors realized that a wide release, supported by national advertising, was more efficient and had more blockbuster potential than the slower local rollouts that had been the norm up until then. This effectively shifted the marketing responsibility from exhibitors to distributors and is the way most films are generally released to this day.

The exceptions to this were and are the art houses, who never lost their energy or ability to market directly to a local audiences. Those of you who are patrons of Laemmle Theaters can see this firsthand, even if you were not aware of how rare this has become. The fact that you reading this right now is an indication that you have a direct relationship with the folks who are running these theaters. This doesn’t happen by accident.

My film is meant to be a tribute not only to one particular person, but all those who are fighting to keep theatrical cinema alive in the face of many obstacles and much negativity. That’s why I’ve made it available to the art houses as a benefit for their post-pandemic reopening. One hundred percent of your ticket dollars will go directly to support Laemmle Theaters. So come on out and lend your support and I hope you’ll find the film to be an inspirational and fun experience.

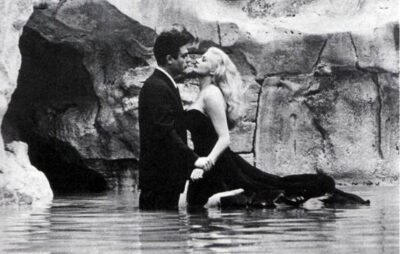

A dreamy fantasia, Annette is French auteur Leos Carax’s English-language debut is a musical whose experimental approach to its emotional extremes is an ambitious return for the director. The screenplay is by Ron Mael and Russell Mael of Sparks and Carax from an original story, music and songs by the band. The plot follows a stand-up comedian (Adam Driver) and his opera singer wife (Marion Cotillard) and how their lives are changed when they have their first child. Writing in New York Magazine, critic Bilge Ebiri called Annette “an altogether weirder, more troubling and personal film than one might expect…this astoundingly beautiful picture will stand the test of time.” Laemmle Theatres opens the film this Friday, August 6 at the Claremont, Glendale, Monica Film Center, Newhall, NoHo, Playhouse and Town Center.

Following are excerpts from interviews with Carax, Cotillard and Driver in the film’s the Cannes Film Festival press book:

Interview with Leos Carax

Q: When did you did you first encounter the music of Sparks?

A: When I was 13 or 14, a few years after I discovered Bowie. The first album of theirs I got (stole, actually) was Propaganda. And then, Indiscreet. Those are still two of my favorite pop albums today. But later, for years, I wasn’t really aware of what Sparks was doing, because by the age of 16, I started to focus on cinema.

Q: And when and how did you meet brothers Ron and Russell Mael?

A: A year or two after my previous film, Holy Motors, came out. There’s a scene in which Denis Lavant plays a song from Indiscreet in his car: “How Are You Getting Home?” So they knew I liked their work, and contacted me about a musical project. A fantasy about Ingmar Bergman, trapped in Hollywood and unable to escape the city. But that wasn’t for me: I could never do something that is set in the past, and I wouldn’t make a film with a character called Ingmar Bergman. A few months later they sent me about 20 demos and the idea for Annette.

Q: What has been your relationship to musical films? Even in your older films it feels like at times musicals are itching to break out of them. You often had these incredible set pieces with characters expressing themselves through song and dance. Is the idea of making a musical something you’ve been thinking about for a long time?

A: Ever since I began making films. I had imagined my third film, Lovers on the Bridge, as a musical. The big problem, my big regret, is that I can’t compose music myself. And how do you choose, work with, a composer? That worried me.

I didn’t watch many musicals when I was young. I remember seeing Brian De Palma’s Phantom of the Paradise, around the same time I discovered Sparks. I eventually saw American, Russian, and Indian musicals later. And of course, Jacques Demy’s films.

Musicals give cinema another dimension — almost literally: you have time, space, and music. And they bring an amazing freedom. You can direct a scene by following the music’s lead, or by going against the music. You can mix all sorts of contradictory emotions, in a way that is impossible in films where people don’t sing or dance. You can be grotesque and profound at the same time. And silence, silence becomes something new: not just silence in contrast with spoken words and the sounds of the world, but a deeper one.

Interview with Marion Cotillard

Q: How much did you like Leos Carax’s films before you came on board for the Annette adventure?

I’m not sure how old I was exactly when I saw Lovers on the Bridge for the first time, but I know I already wanted to be an actress. I’d loved the film, its gracefulness, its poetry – I was overwhelmed. But then again, there was Juliette Binoche whose character, performance, and radiance swept me off my feet at the time. I fell in love with Leos Carax’s artistry, and I saw all of his films over time, up until his latest, Holy Motors, which I think is a masterpiece.

Q: Annette‘s script is a very peculiar affair, halfway between a traditional narrative and an opera libretto, accompanied by Sparks’ songs. How di you react when you first read it?

A: When I received the script, I already knew the film was entirely sung, and the narrative was only made up of songs. I was already sold, as it were. I felt so lucky to be able to lay my hands on this piece. And then I was totally won over as I read it – I related both to the uplifting element of the operatic musical and the profound darkness of what the film is about.

Q: Did you still hesitate in any way before embarking on the project?

A: I immediately wanted to work with Leos, but I wasn’t sure I could bring all that the character required. Leos is a rare filmmaker and makes very few films. It necessarily adds to the pressure, to the fear of not being able to match up to him as an artist. So I did hesitate a little. I asked my singing teacher if I could in no time learn how to live up to what was expected of me, even though I obviously couldn’t possibly become an opera singer in just a few weeks. We knew from the outset that we had to come up with a method for the opera singing part – and blend my voice with that of a professional singer. Still, it was a huge challenge. My teacher told me it’d be difficult, it’d take a lot of work, but that we could be confident. I needed his blessing to say “Yes.”

Q: How familiar were you with Sparks’ music before working on this project? How does it inspire you?

A: I wasn’t familiar with their music at all but as a teenager, I just loved Rita Mitsouko’s “Singing in the Shower” and I found out later it was written by Sparks. Then I met with them for this project – and I was overwhelmed by their commitment to and faith in the film. Sparks has always been involved in the project, from its early days. There’s something liberating when you actually get down to work, for artists who have been a part of this project for so long, who fought to bring it to completion. The film was getting made, and they knew it, and we all shared in the joy of working all together for the benefit of a special project and of special artists.

Q: Leos Carax is best known for being a painstaking filmmaker on set and for addressing the actors almost by whispering into their ears. Did you experience that yourself?

A: He’s both very specific on set and very flamboyant. He’s totally in love with his job, with the set, with the filmmaking process, the actors, and he’s highly respectful – as an actor, it’s wonderful to feel watched and cared for by an artist such as him. What struck me on set is how much he keeps track of every detail – how well a piece of clothing fits, how you convey what you intend to portray and so forth. He was so focused, and all the more so as the shoot was particularly challenging because Leos was intent on having all the songs performed live. On most traditional musicals, you record your songs during preproduction and then you lip-sync on set. But on this project, Leos wanted everything to be live. It made the shoot even more challenging – we’d be singing in very awkward positions, like backstroking or faking cunnilingus, which are very challenging postures that technically affect your singing. But this is the kind of effect Leos was looking for – he wanted voices to be altered, thwarted by reality.

Q: Tell us about your approach to singing and music, precisely. How did you work with the singer Catherine Trottmann, whose voice was blended with yours for the opera singing part?

A: We knew from the start that I couldn’t take on the opera singing all by myself. It’s just impossible to reach a soprano’s vibrato in barely three months of training. So we decided to blend my voice with that of a professional singer, but we only found her after we wrapped the shoot, which made things even more difficult. I had a wonderful time with Catherine Trottman as I almost found myself in the position of a film director

– I’d give her directions on how to adjust her voice, on the songs’ meaning etc. It was both complicated to pass on part of my performance to someone else and extremely inspiring.

Interview with Adam Driver

Q: What was it about the project that made want to be a part of it, not only as an actor but as a producer?

A: That it was Leos. That it was a musical the Sparks wrote. There were all these big sequences that required rehearsal, big set pieces, a lot of moving parts. All of it sounded like a challenge but that the result could be singular.

Q: What was it about Leos Carax’s previous work that made you interested in collaborating with him? Were there any films of his that you particularly liked or were inspired by?

A: The actors seemed to have such freedom in them. And the shots are incredible. They ask a lot of the people making them. Hard to pick a specific one. There are moments and sequences in all of them that are unforgettable.

Q: What was Leos’ directing style like on set?

A: Hard to summarize but from my perspective he’s living every moment along with his actors and crew; so he’s not leading with a bullhorn, it’s more from a place of focus. He’s doesn’t miss a detail. He’s great at balancing moments of complete spontaneity within heavy choreography. He’s hilarious. He’s one of the great directors of all time.

Q: Much of the dialogue is sung. What did you do to prepare for the musical aspect of the role? What was the rehearsal process like?

A: As far as the music was concerned, I met with Michael Rafter, who I had worked with on Marriage Story. I drilled the songs with him for months. The Sparks and Leos were very clear with what sound they were going for and that the storytelling was the priority. We pre-recorded everything as a back-up but we sung everything live as well. I don’t know what percentage made it in the movie but I think the majority.

Roy Andersson is one of the world’s most eminent living film directors, and the main subject of Being a Human Person. This maverick Swedish auteur’s work has been celebrated at all of the world’s major film festivals, from his 1970 debut A Swedish Love Story, which picked up four prizes at Berlin, through to Songs from the Second Floor, which won the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival in 2000. His final two films (A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence and About Endlessness) both premiered in Venice, winning the Golden Lion in 2014 and Silver Lion in 2019, respectively.

At 76 years of age, Andersson was about to complete his final film, About Endlessness. With the end of his career in sight, the central thematic concerns of his work – vulnerability, insecurity and mortality – spilled over into his creative process, blurring the line between the personal and the professional. In documenting this process, Fred Scott’s Being a Human Person becomes a powerful meditation on the relationship between art and artist, and a heartbreakingly honest portrait of one of the most startlingly original and unremittingly humane directors in world cinema. Laemmle Theatres opens Being a Human Person on our virtual platform beginning this Friday, July 30. About Endlessness is available now.

The British production company Archer’s Mark wrote the following about the documentary:

There are some filmmakers whose style is so unique, they can announce themselves in a scene. Lynch, Spielberg, Welles, Malick. They have such intense and personal vision, such specificity of time, place and cultural context – that we only need to spend a minute in their world to recognise their signature. And then there is Roy Andersson. A director who possesses a style of visual storytelling that allows his work to be known in a single frame.* Because Roy – in a world where the hyperbolic use of such a phrase is all too commonplace – is truly one of a kind, for many reasons.

Each of his films takes an average of five years to make. His crew builds every set; films it; and then destroys it. He uses only fixed, long shots with no close-ups or edits. Each film is made up of an average of 40 intricate, painterly tableaux. He only casts non-professional actors. Roy’s intricate in-camera trickery employs surgical craftsmanship that is meticulous to the point of madness… And all of this takes place on the two floors below Roy’s apartment in an unassuming townhouse in central Stockholm – also known as the legendary Studio 24.

In short, Roy’s way is the antithesis of every film production of the last 50 years. It has won him garlands at the biggest festivals in the world – Cannes, Berlin, Venice – and the adulation of visionary directors like Darren Aronofsky and Alejandro G. Iñárritu.

In an age of the franchise, and a proliferation of cookie-cutter storytelling, Roy is quite simply the last of his kind. And now, at 76 years of age, he is about to present his last film to the world. That film – About Endlessness – will mark the end of a major chapter in cinema. For when Roy stops making films, they will simply never be made in this way again.

Set across a three year time period, Being a Human Person charts the arduous and unsettled arc of production of what Roy lovingly terms his “final effort”. Shot through with Roy’s candour, humour and insistence on capturing the process in all its truthfulness – even as he comes to terms with his own, increasingly fragile, mortality – it also becomes a meditation on the legacy of a master storyteller as he calls time on his career.

*From The Living Paintings of Roy Andersson by Film Qualia (YouTube)

Legendary actor Udo Kier stars as retired hairdresser Pat Pitsenbarger, who escapes the confines of his small-town nursing home after learning of his former client’s dying wish for him to style her final hairdo. Pat embarks on an odyssey to confront the ghosts of his past — and collect the beauty supplies necessary for the job. Swan Song is a funny, bittersweet journey about rediscovering one’s sparkle, and looking gorgeous while doing so.

Writer-director Todd Stephens wrote the following about his new film:

“Back in 1984, I walked into my small-town gay bar for the first time — The Universal Fruit and Nut Company. There he was, glittering on the dancefloor. Wearing a teal feather boa, fedora and matching pantsuit, “Mister Pat” Pitsenbarger was busting old school moves straight out of Bob Fosse. I was seventeen, and Pat was a revelation.

“Years later, when I set out to write my autobiographical Edge of Seventeen, I immediately thought of Mister Pat. I went back home to hunt him down, only to discover Pat had just suffered an aneurism and was temporarily unable to speak. But his lover David told me stories…about how Pat was once the most fabulous hairdresser in Sandusky, Ohio…about his legendary drag performances…about how he used to shop at Kroger’s dressed as Carol Burnett – in 1967! This was a man who always had the courage to be himself, long before that was safe.

“The truth is, Mister Pat inspired me to write Edge of Seventeen. I wrote a significant “Pat” character as my protagonist’s mentor, but midway through the shoot, the part got cut. I always knew my muse would return someday in my writing, and when he finally did many years later, I looked for Pat again only to learn he just passed away. Sadly, Pat’s legendary hand-beaded rhinestone gowns are all lost to time. Only a shoebox remains – filled with some tarnished jewelry and a half-smoked pack of Mores.

“Swan Song is a love letter to the rapidly disappearing “gay culture” of America. As it has become more acceptable to be queer, what used to be a thriving community is rapidly melting back into society. Thanks to assimilation and technology, small-town gay bars like The Universal Fruit and Nut Company are becoming extinct. Swan Song is dedicated to all the forgotten flaming florists and hairdressers who built the gay community and blazed the trail for the rights many of us cling to today. But, above all, for me this film is about learning that it’s never too late to live again.”

Laemmle Theatres will open Swan Song on August 6 at the Playhouse, Royal and Town Center.

On Friday, July 30 we’ll open the Nigerian drama EYIMOFE (THIS IS MY DESIRE) at the Royal. A triumph at the 2020 Berlin International Film Festival, the revelatory debut feature from co-directors (and twin brothers) Arie and Chuko Esiri is a heartrending and hopeful portrait of everyday human endurance in Lagos, Nigeria. Shot on richly textured 16 mm film and infused with the spirit of neo-realism, Eyimofe traces the journeys of two distantly connected strangers—Mofe (Jude Akuwudike), an electrician dealing with the fallout of a family tragedy, and Rosa (Temi Ami-Williams), a hairdresser supporting her pregnant teenage sister—as they each pursue their dream of starting a new life in Europe while bumping up against the harsh economic realities of a world in which every interaction is a transaction. From these intimate stories emerges a vivid snapshot of life in contemporary Lagos, whose social fabric is captured in all its vibrancy and complexity. traces the journeys of two distantly connected strangers—Mofe (Jude Akuwudike), an electrician dealing with the fallout of a family tragedy, and Rosa (Temi Ami-Williams), a hairdresser supporting her pregnant teenage sister—as they each pursue their dream of starting a new life in Europe while bumping up against the harsh economic realities of a world in which every interaction is a transaction. From these intimate stories emerges a vivid snapshot of life in contemporary Lagos, whose social fabric is captured in all its vibrancy and complexity.

Writing at Film Threat, Hanna B. called EYIMOFE “a touching, beautiful, and complex tableau about how to overcome adversity and seek opportunities when you are at an impasse: a Nigerian story, an African story, a migrant story, a human story.”

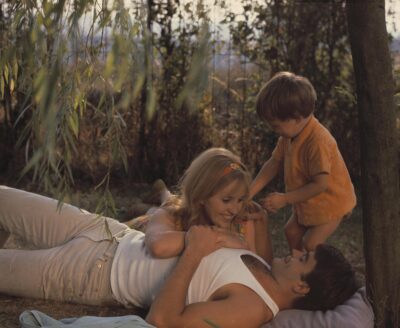

It’s the 20th anniversary of Alfonso Cuarón’s impossibly sexy, funny Y TU MAMÁ TAMBIÉN, which we’ll screen on December 8.