This week and next we’re delighted to show the sui generis farce Hundreds of Beavers. The March 14 Hundreds of Beavers screening at the Royal, March 15 & 16 late shows in Glendale, March 18 at the NoHo, and March 19 in Claremont will feature Q&As with the filmmakers plus a beaver or two.

The screenings have become something of a phenomenon, so much so that the New York Times posted a story about them last week. It begins:

“Last week, a bonkers low-budget movie that was shot in black and white and has no Hollywood stars, packed a 200-seat theater on a one-night engagement at the IFC Center in Manhattan. Additional screenings were added.

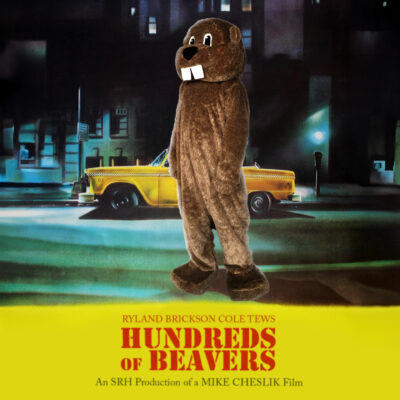

“Mike Cheslik, the film’s director, and Ryland Brickson Cole Tews, its leading man, don’t have Hollywood connections or sacks of cash. What the two 33-year-old friends do have that helped their film make a splash with its New York debut is a secret weapon that would make a shrewd old-school movie pitchman like William Castle tingle with envy.

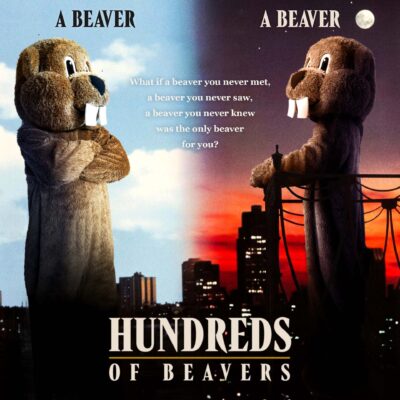

“We’re talking beavers. Big ones.

“Two life-size beavers, actually — plus a horse, all played by humans — who took selfies with passers-by on the sidewalk and high-fived audience members in their seats before a screening of Cheslik’s frolicsome farce Hundreds of Beavers.

“At a time when Hollywood and scrappy filmmakers alike are stressing over how to get butts into seats, Cheslik and Tews are counting on a live make-believe beaver fight — a marketing gimmick dressed like a vaudeville act — to sell their movie.” Read the rest of the article here.

The filmmakers and distributor have a genius for marketing, as evidenced by some of the parody posters they’ve assembled:

However, this is not just hype; Hundreds of Beavers is good. As of this writing, it’s at 98% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes.

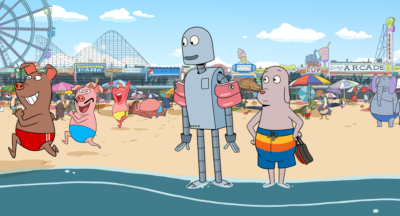

“A soulful silliness pervades the rootin’, tootin’ live-action cartoon Hundreds of Beavers from Milwaukee filmmakers Mike Cheslik and Ryland Brickson Cole Tews, merry pranksters who deploy a gleefully inventive lo-fi madness to their gag-stuffed wilderness comedy. Pitting a lovestruck fur trapper against a bucktoothed horde, this underground festival hit is a feverish fit of creative buffoonery — you haven’t experienced anything remotely like it.” ~ Robert Abele, Los Angeles Times

“On paper, it would hardly be expected to remain funny for eight minutes, let alone 108. But this ingeniously homemade lark never runs out of steam.” ~ Dennis Harvey, Variety

“Hundreds of Beavers starts strange, gets stranger, and yet remains resolutely adorable.” ~ Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, AWFJ.org