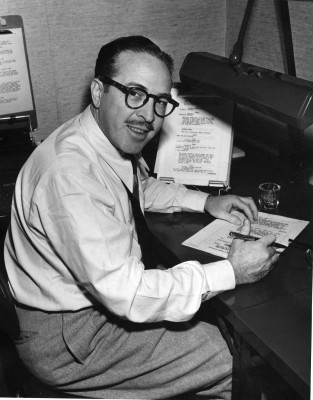

The terrific fine arts blog arts•meme, published by longtime dance critic Debra Levine, gave our Anniversary Classics screening of SPARTACUS a nice plug last week. We’re showing it this Friday night November 6th at 7:30 in the Royal’s big auditorium on the same day that Trumbo opens in theaters. (We open it a bit later.) The new film celebrates the life of Dalton Trumbo, and with this 55th anniversary screening of their Oscar-winning film we pay our own tribute to the blacklisted screenwriter, as well as actor-producer Kirk Douglas and director Stanley Kubrick. The picture, adapted from Howard Fast’s novel about a slave revolt in ancient Rome, is generally regarded as “the best-paced and most slyly entertaining of all the decadent-ancient-Rome spectacular films,” as critic Pauline Kael wrote. Douglas bravely decided to break the blacklist by allowing Trumbo to use his own name on the screenplay for the first time in more than a decade.

The terrific fine arts blog arts•meme, published by longtime dance critic Debra Levine, gave our Anniversary Classics screening of SPARTACUS a nice plug last week. We’re showing it this Friday night November 6th at 7:30 in the Royal’s big auditorium on the same day that Trumbo opens in theaters. (We open it a bit later.) The new film celebrates the life of Dalton Trumbo, and with this 55th anniversary screening of their Oscar-winning film we pay our own tribute to the blacklisted screenwriter, as well as actor-producer Kirk Douglas and director Stanley Kubrick. The picture, adapted from Howard Fast’s novel about a slave revolt in ancient Rome, is generally regarded as “the best-paced and most slyly entertaining of all the decadent-ancient-Rome spectacular films,” as critic Pauline Kael wrote. Douglas bravely decided to break the blacklist by allowing Trumbo to use his own name on the screenplay for the first time in more than a decade.

The all-star cast includes Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Jean Simmons, Tony Curtis, Woody Strode, and Peter Ustinov, who won the Academy Award for best supporting actor for his droll performance as a sycophantic slave dealer. (The film also won Oscars for cinematography, art direction, and costume design.) See this grand, thrilling sand-and-sandals epic—a precursor of Ridley Scott’s Oscar-winning Gladiator—on the big screen, in a brand new restoration.

The all-star cast includes Laurence Olivier, Charles Laughton, Jean Simmons, Tony Curtis, Woody Strode, and Peter Ustinov, who won the Academy Award for best supporting actor for his droll performance as a sycophantic slave dealer. (The film also won Oscars for cinematography, art direction, and costume design.) See this grand, thrilling sand-and-sandals epic—a precursor of Ridley Scott’s Oscar-winning Gladiator—on the big screen, in a brand new restoration.