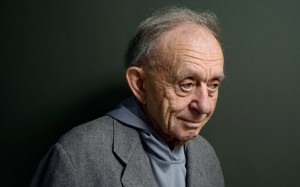

Documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman, now in his sixth decade of filmmaking, always gets good reviews but his latest, a film that immerses its audience in London’s National Gallery and we open November 21 at the Royal Theater, is garnering raves. From Manohla Dargis at the New York Times (“Like most of Mr. Wiseman’s work, the movie is at once specific and general, fascinating in its pinpoint detail and transporting in its cosmic reach.”), to Tim Grierson at Paste Magazine (“Nourishing and enthralling, NATIONAL GALLERY is the work of a man still invested in the arts, in the world and in people.”), to David Denby at the New Yorker (“Holds the movie viewer in a state of intense and pleasurable concentration”), even the toughest of critics are telling us that Mr. Wiseman’s latest is not to be missed.

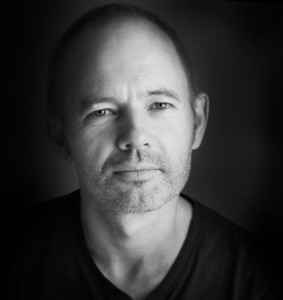

The Daily Beast just published a good piece about the film by Tim Teeman:

Inside The Secret World of London’s National Gallery

Read the complete Daily Beast piece by clicking here.