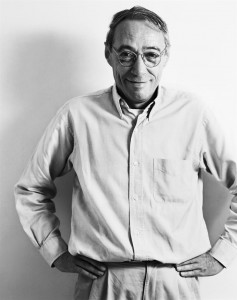

This month we’ll be opening the intense new French thriller IN THE NAME OF MY DAUGHTER, (originally L’homme qu’on aimait trop). Directed by master André Téchiné (My Favorite Season, Wild Reeds), Catherine Deneuve stars as a glamorous casino owner in 1970s Nice. The drama begins when her daughter (Adèle Haenel) moves back home, falls in love with her mother’s formerly trusted adviser (Guillaume Canet), commits a major betrayal and then disappears. Thirty years later, her mother is determined to see justice done. M. Téchiné sat for an interview about his latest film:

The film started out as a commission. What did they want you to do?

Originally, the idea was for me to make a loose adaptation of Renée Le Roux’s memoirs, Une femme face à la mafia (lit: A woman up against the Mafia) written by her son Jean- Charles. From the outset, I knew that I wanted Catherine Deneuve to play the part of Renée Le Roux. The book tells the story of the casino wars on the French Riviera between the 1970s–1980s, from the protagonist’s point of view. It includes the account of the take-over of Madame Le Roux’s Palais de le Mediterranée casino by Jean-Dominique Fratoni, with the support of Jacques Medecin, the then-mayor of Nice. The casinos in this story are a far cry from the casinos of today. In fact, some of the most popular ones, like the ntc33, operate solely as online casinos now. It adds to the growing list of online casino websites that players can enjoy from the comfort of their own homes. Casinos are becoming more accessible, with some allowing their users to play and deposit with phone credit and other amenities. However, this abundance of online casinos isn’t necessarily a good thing. Back in the 1970s-1980s, when the story was set, you knew how good a casino was because of its reputation. You could guarantee that lots of people would have visited them and could give an opinion on them. Today, there are so many online casinos, meaning there will be many which won’t have been played by people you know, so you won’t know how good they are. This is where sites like Casino Martini come in handy; they review online casinos like Barbados so you know which ones are best to use.

What interested you about this story?

I focused my attention on the relationship between Renée Le Roux, her daughter Agnès, and Maurice Agnelet: the iron-fisted mother, the rebellious daughter and Agnelet’s desire for recognition by society. It was Agnès that I was most interested in. I wanted to paint her portrait. I agreed to make the film after reading the letters that Agnès had written to Agnelet because, quite unexpectedly, I found a surprising resemblance with another female character that I had long wanted to bring to the screen, Julie de Lespinasse. There are many parallels between the passionate love letters of this woman of letters and Agnes – heir to the Palais de la Mediterranée’s – letters. For example: “I love you how you must be loved, with excess, madness, ardor and despair.”

You turned the story of the casino wars into a story of psychological confrontation that takes on a myth-like status.

This is a war film. But on a human level. I was determined not to remove the events that drive the plot. I wanted to show the process of a takeover of power, the methods used to bring down a casino, the workings of a business in this very shady environment with all the elements of cruelty and servitude. I wanted to follow through on all the events that really happened until the downfall, until defeat. This war-like aspect structures the narrative.

How did you write the screenplay?

I started out writing the screenplay with Jean-Charles Le Roux, who had all the facts to hand. We wrote a treatment, outlining a detailed sequence of events to give the film a clear structure. Jean-Charles Le Roux was involved alongside his mother in the struggle to get Maurice Agnelet convicted. He was convinced that Agnelet had murdered Agnes. I made it clear to Le Roux that I was not going to make a film that incriminated Agnelet. This remained a very sensitive issue during our time spent working together. Then I worked with the filmmaker Cédric Anger on a second version of the film to help flesh out the scenes.

Did you change any of the facts in order to strengthen the dramatic impact the film might have?

We tried to simplify the plot, notably by removing the characters of Agnès’s brothers and sisters as well as Agnelet’s son’s two brothers (there was not enough time to explore them all). We did this to reinforce the three main characters of the plot and create a central ‘triangle’ of relationships. As to the order in which the events take place, we only allowed ourselves one change: in real life, the closure of the casino and the subsequent occupation by the staff took place later on. Dramatically speaking, I felt that it was more important to tell the story of the “fall” of the Palais de la Mediterranée casino in the same time frame as Agnes’s disappearance.

You also had to decide up to which point you were going to tell the story, beyond Agnès Le Roux’s disappearance in November 1977.

For a long time, it wasn’t my intention to dramatize the court case. I harbored bad memories about films where the action takes place in courtrooms. The first time I was truly bored at the cinema was when I went to see André Cayatte’s film Justice is Done– but there are a lot of good films about court cases too, especially American ones. Anyway, it became clear that it was impossible to ignore the judicial aspect. Renée Le Roux’s determination to see Maurice Agnelet convicted was a key part of this story. For her, it was the crux. And, the justice system and its contradictory decisions constitute the official outcome of this case.

Justice, also meaning the fact of deciding once and for all what is true and what isn’t.

Yes, although in this particular case, we don’t really know the truth. There is no body, no crime scene and no real evidence. A lot of the material used during the court hearing was circumstantial or inadmissible. For example, the prosecution said that because Agnelet didn’t leave a message on Agnes’s answering machine out of concern for her welfare when she went missing, proves his guilt. But you could equally turn this argument around and say that a murderer might leave messages to cover his tracks. There were lots of inconsequential lines of discussion like that in the trial.

You never envisaged changing the names or turning the film into a fiction?

No. It was important to stick to the real narrative. It’s a way of saying that real tragedy takes place in our world. Incidentally, Guillaume Canet was in touch with Maurice Agnelet, and he told him about the conversations he had with Agnès, after the shares in the casino were sold, and when the press accused Agnes of betraying her mother and she was so desperate. Those are words that I could never have made up, but that I chose to be spoken by the character. It would have been absurd to change the names, and not anchor this unbelievable story in what is its real framework.

Your film The Girl on the Train was also based on a well-known news story. Are there any similarities in the creative process in these two films?

What they have in common is that they are both based on extraordinary events that really did happen: real-life dramas. But the stories and themes are very different. The Girl on the Train was about how lying can be a means to hide suffering. In the Name of My Daughter is about a 3-way power struggle.

You chose not to include the more overtly political dimension that is in the book Une femme face à la mafia (lit: A woman up against the Mafia) in which Jacques Médecin is one of the central characters.

Everything in the book is there in the film. I didn’t exclude any part of the book, including this element, but my film focuses on Agnès Le Roux’s disappearance. Still today, there is no actual proof that her disappearance was linked to the mafia. This film is undoubtedly political, but not at a grass roots level. What I show is a social class in turmoil, its turf wars, its calculating, predatory nature; all of this is ‘political’ in this story about inheritance. The film shows the way in which the people caught up in this are affected.

Money and the hunger for power are clearly at the centre of this story, but there is something more, in the subconscious, something impulsive. For example, when Agnes launches into an African dance that becomes a trance.

This moment in the film illustrates Agnès’s unwillingness to conform. Here she uses her body to express herself freely in contrast to the restrictive discipline of ballet that was part of her early education. She is asserting her independent nature. It is an escape, a release. It’s very striking.

How did you decide how the film should look?

For the scenes that take place in the casino, I wanted it to look very European, a sort of anti-Las Vegas. In complete contrast to the set design of Scorsese’s – splendidly filmed – Casino. Olivier Radot and I imagined the work of the artist Klimt, and his depiction of bejewelled women and Orientalism. For Catherine Deneuve’s costumes, Pascaline Chavanne took inspiration from Jacques Demy’s Bay of Angels and Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Gesture. In the same way that the set design and the costumes were fantastical, the light in this film acts as a smokescreen. It is similar to that used for say a sophisticated comedy set on the French Riviera. The production values disguise the inherent violence that is to unfold. It’s camouflage. Behind it lies tragedy. I wanted to swim against the tide and against the oppressive nature of such a dark tale. Despite the inevitability of this true story, I wanted to make a film where the mood appears ‘light’, a daylight film where there are practically no scenes shot at night. I wanted to exaggerate the brightness of the colors and the camera movements. I wanted scenes where we filmed the sea and went up into the mountains.

A large part of the complexity and the appeal of this film relies on the character of Agnès Le Roux. How did you choose the actress to play her part?

I had been following Adèle Haenel’s (Water Lilies. Love at First Fight) work for some time. I knew that she was a beautiful and powerful young actress. I had seen her play girls from working class backgrounds and I liked the idea of offering her the part of a rich young heiress, and being the daughter of Catherine Deneuve. She has such wonderful natural elegance. And she knows how to be tough. She has Agnès Le Roux’s athletic build, with a mix of vitality and a hint of madness, and is very impetuous: she’s straight up, no frills, a whirlwind of youthful energy. Agnes Le Roux is the antithesis of your average victim: she’s active, sporty; she wants to work and open her own shop. She’s not some fragile little thing, and is a far cry from your archetypal spoilt child. There is something very radiant about her, which, I think I’m right in saying, comes across even more effectively with her hair dyed brown.

In the Name of My Daughter is your seventh film with Catherine Deneuve. What is particular about this role?

It’s the first time that Catherine Deneuve has been asked to really exaggerate the role of masquerade and sophistication in one of my films. We had such fun with her spectacular outfits and she never wore the same thing twice. Madame Le Roux, who was once a cat walk model for Balenciaga, was always ‘on show’ at the Palais de la Mediterranée casino before she took over the running of it, under the influence of Agnelet.

Dressing up was part of her social ritual. Renée is like a goddess watching over her kingdom. But at the same time Renée Le Roux is probably the most resilient character out of all the characters Catherine Deneuve has ever played in my films. This character appears dominant, determined and ruthless and is the total opposite of the instability that was our chosen register (to capture the elusive). The only precedent I can think of, out of all of her roles in fact is that of Tristana in the last part of Bunuel’s film, when she plays a very hard old woman. In In The Name of My Daughter, she goes further. She is furiously determined; she wants Agnelet’s head on a plate. Despite her age, she is as strong as an ox.

And Guillaume Canet?

I had wanted to work with him for a very long time. To play Agnelet, we needed an actor who was very attractive but who was also “ideal son-in-law” material. The part required that the actor went behind the pretense and revealed the other darker side of his nature. I had seen Guillaume Canet play sympathetic roles, but I knew he was also capable of being disconcerting, of obscuring the truth and of being unnerving, a bit like Cary Grant in Suspicion (what exactly has he got in mind?). That’s what interested me about the real Agnelet. A man who protects himself from his own feelings, a closed book, whilst all the while being charming and seductive. Guillaume managed to bring all of these facets together in the role. He wasn’t frightened of being subservient to Renée Le Roux and Fratoni. He wasn’t frightened of being sadistic and cruel with Agnes. He took on the cowardice and cruelty of the character, never looking for pity or affection. Agnelet is an orchestrator: he gets people to play a part; he manipulates them and then records them. But he trips up and falls into the trap of his own lies. He is his own worst enemy. That is his tragic side. During his last trial it was his own son (and supporter) who accused him of murdering Agnès. Behind his Don Juan smile he reminds me of a quote from Pascal: “The twofold nature of man is so evident that some have thought that we had two souls.”